Picture yourself in a regenerative city, where even an ordinary public square responds to climate change and community life together.

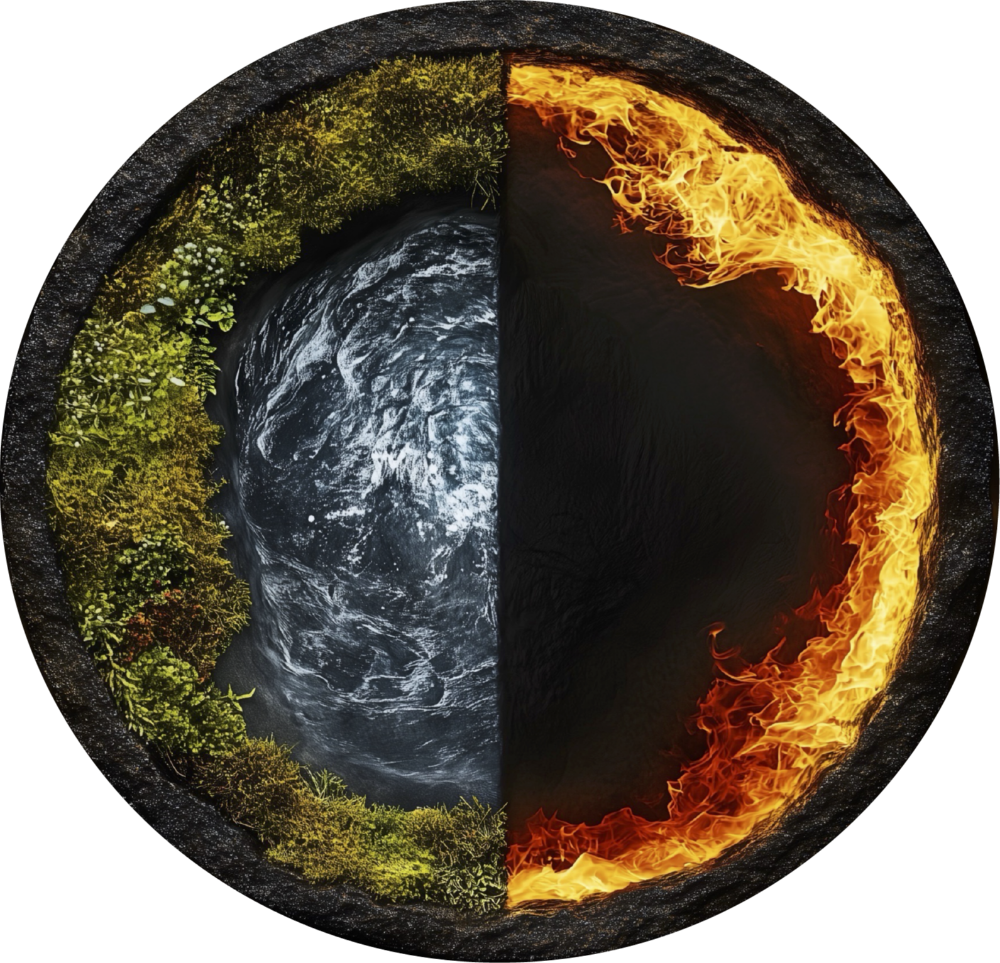

Cities are where the fate of life in this century will be decided. Today they concentrate extraction, pollution, and waste; tomorrow they can become engines of regeneration. A regenerative city runs on renewable energy, with quiet, clean mobility and breathable air; it produces food close to home, restores water and soil, and replaces linear waste with circular systems of reuse and composting. Buildings, streets, and infrastructure participate in living systems—cooling urban heat, buffering floods, supporting biodiversity, and adapting to intensifying climate disruption. Streets belong to people rather than cars; former roadways become green corridors, and cities are designed to be traversed by humans, animals, and flowing water alike. Within this larger transformation, everyday places offer tangible proof: a public square where families move at ease, children invent games at a play structure, café conversations hum, and a steady stream of visitors passes through a local tool and seed library. Curved rows of native plants and pathways ring a central fountain that filters and diverts stormwater; monarchs drift through pollinator corridors; most people arrive on foot or by bike along protected lanes. Beneath the surrounding shops, vehicles recharge quietly underground, while rooftop solar powers local businesses above. These are not isolated design flourishes but local responses to global climate change—places where ecological regeneration and human flourishing unfold together, and where cities become living laboratories for a resilient, regenerative civilization.

[then go to ending paragraphs]

or

It is designed as a resilient, living system—one that supports local biodiversity, regenerates water and soil, actively contributes to carbon sequestration, and strengthens community flourishing. Curved rows of native plants and pollinator gardens surround a central water feature that doubles as stormwater infrastructure, channeling heavy rainfall through permeable pathways and micro-wetlands. The design cools the urban microclimate, buffers heat waves, and provides refuge during extreme weather—local responses to global climate change built directly into the landscape. Families move easily through the space; children play at sculptural structures; cafés spill out into steady conversation. The square serves as a learning hub for schools, with a tool and seed library that strengthens community skill-building and cultural resilience. Monarchs drift along protected corridors as visitors arrive by foot or bicycle, while underground charging stations and rooftop solar power the surrounding businesses. This square shows what becomes possible when a community invests in biodiversity, climate preparedness, and ecological wellbeing—offering a glimpse of the future we help design, one watershed and one neighborhood at a time.

Families move about leisurely. Children laugh and invent games at a play structure. Conversations hum on the patios of cafés lining the square. A steady stream of visitors flows in and out of the local tool and seed library. Curved rows of native plants and pathways ring a central fountain, the artistic landscaping helping to filter and divert rainwater during storms. Passersby marvel at the number of monarch butterflies present. Most people arrive on foot or bicycles, dismounting at the end of protected bike lanes. Beneath the shops surrounding the square, cars recharge at electric charging stations in underground parking. Atop the buildings, solar panels quietly and cleanly power local businesses.

[closing]

We believe a reality like this is still possible, but we also know that it feels ever more distant for sustainability practitioners in the US, whose federal government has abandoned climate action and environmental protection, doubling down on burning more fossil fuels while deepening environmental injustice and human rights abuses. Our colleagues working for clean air, water, and energy are overwhelmed and under-resourced.

We can and must navigate this terrain, but conventional methods of planning, strategy, communication, and community engagement aren’t working. In our work across local government, nonprofits, and higher education, four often overlooked elements have helped us—and our clients—achieve results:

1. Ensuring Material Impact

The first element involves ensuring material impact. While colorful dashboards, sophisticated financial incentives, and lengthy climate action plans have a function, often more time and money are invested in these products than in earthy, tangible outcomes. Multi-year planning efforts become obsolete by the time of adoption, and new planning cycles begin soon thereafter.

Ensuring material impact involves two parts. First, when you hire us, we work to ensure that what we deliver sets you up to achieve material results, so that your plans, strategies, and engagement lead directly to new rain gardens, complete streets, and solar farms. Second, we encourage organizing work around tangible boundaries like neighborhoods, watersheds, and mountain ranges that people can see and feel rather than arbitrary administrative borders or subdivisions.

This approach aids community engagement by locating sustainability within the living systems that sustain human and more-than-human communities. It grounds sustainability in the lived reality of a place, building resilience by aligning governance, culture, and ecology at the scale where life actually unfolds.

2. Leveraging Psychology

The second element leverages psychology, which we do in three ways. First, we include time to address your frustration, grief, or anger as a sustainability practitioner who is committed to caring for the Earth. We examine how these emotions create unseen barriers for our work and how processing these feelings can unlock greater effectiveness.

Second, we incorporate the findings of climate psychology into the process and products we deliver. Research on what people feel and believe about climate change has proliferated in recent years, yet psychologists’ discoveries rarely reach the desks of sustainability practitioners, much less inform local work.

Third, we leverage the iceberg model to understand the patterns, structures, and mental models beneath events—like a community engagement meeting with disappointing attendance. When undertaking community engagement, many consultants treat these events as checkboxes. We design the format, framing, and facilitation to invest in relationships, forge partnerships, and yield feedback that is genuinely useful.

3. Creating Space for the Unknown

Real innovation and regeneration require room to breathe. Creativity requires that we release certainty, pause habitual motion, and allow the unknown to enter. It is the discipline of letting go—of assumptions, clutter, control, and even success stories that no longer serve.

In sustainability work, there’s a deep pressure to “know,” to always have the next plan, the next answer, the next funding stream. Yet true transformation often begins with not knowing, letting silence and openness reshape what’s possible. Like a winter field lying fallow, this element invites us to stop producing for a season so something unseen can take root. Practically, this might mean “clearing the deck,” as Zen teacher and Indigenous elder Norma Wong puts it, or “waiting for the tide” before taking action.

Sometimes the wisest action is subtraction. In a culture of overproduction and ever more choices, this might mean closing old programs, simplifying processes, or pausing before rushing to the next initiative. It can also mean removing options as much as adding new ones—banning new gas hookups (not just incentivizing electrification) or removing lanes of automobile traffic (not just adding bike lanes).

Creating space for the unknown also invites government teams to become lighter, freer, and more lucid—like the open sky after a storm. When staff let go of excess, they create the clarity and freedom from which truly fresh ideas, partnerships, and ecological insights can emerge.

4. Slowing Down to do What’s Needed

Not all effective action is fast. Rivers reshape mountains through patience. Glaciers carve valleys without haste. In human systems, the capacity to slow down, feel, and flow (like water) cultivates rest as a foundation for wise, adaptive movement. Even the army knows this: “slow is smooth; smooth is fast,” they say.

This century’s environmental movement experiences a constant state of urgency: impending global thresholds, billion dollar disasters, pressure from stressed communities, grant deadlines and reporting cycles with never enough money. This “crisis epistemology,” as Indigenous philosopher Kyle Whyte calls it, can trap institutions in perpetual emergency mode, reacting to symptoms rather than flowing towards long-term resilience.

Slowing down shifts us from reactivity to responsiveness so we can perceive and act with interconnection, timing, and flow.

This crucial element of our work embodies what Daoist traditions call wu-wei—effortless action that arises from being attuned rather than controlling. From the standpoint of organizational psychology, this resembles a flow state—deep engagement where awareness and action unify, and creativity moves without strain.

Like a river carving stone, the power of water is not brute force but persistence. In a world obsessed with urgency, slowing down can help climate action be more fluid and adaptive—able to move around resistance, shape the policy landscape over time, and flow steadily toward enduring change.